Bazerman helps you how to recognize your own blind spots and how to avoid the habits that lead to poor decisions and ineffective leadership in the first place.

Every one had a negotiation fall apart or had it provide a less positive outcome than hoped for. Often this is because a critical piece of information and detail was missed or overlooked. How can you avoid that from happening again? Should you have noticed?

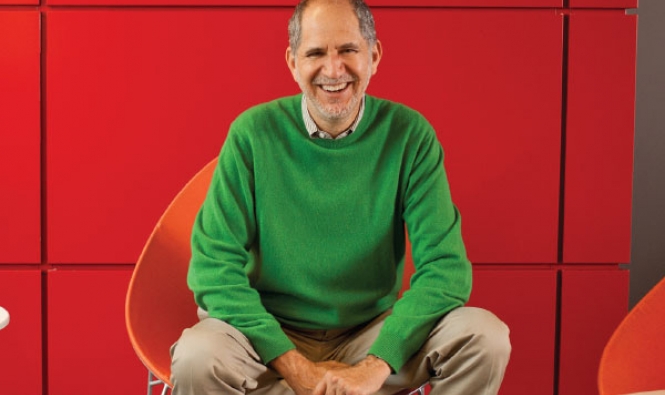

Max Bazerman, an expert in the field of applied behavioral psychology, draws on three decades of research and his experience instructing Harvard Business School MBAs and corporate executives to teach you how to notice and act on information that may not be immediately obvious. Bazerman suggests you explore your cognitive blind spots, identify any salient details you are programmed to miss, and then take steps to ensure it won’t happen again.

In psychology a blind spot is defined as aspects of our personalities that are hidden from our view. These might be annoying habits like interrupting or bragging, or they might be deeper fears or desires that are too threatening to acknowledge. One place that blind spots can be found is in strong reactions. An unusually strong negative or positive reaction or stance may suggest an engagement in a process Freud called reaction formation. Reaction formation involves unconsciously transforming an unacceptable or undesirable impulse into its opposite. This tendency is not confined to sexuality. Harsh judgments of others’ behavior may show a personal insecurity – such as, that highly ambitious co-worker may especially irritate you because of your own unexpressed ambitions. Blind spots in these cases need not be objectively negative traits, just traits that are experienced as personally shameful or unacceptable. Full Article

Simine Vaziere stated in an abstract of her research: “According to the self-other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model, the self should be more accurate than others for traits low in observability (e.g., neuroticism), whereas others should be more accurate than the self for traits high in evaluativeness (e.g., intellect). In the present study, 165 participants provided self-ratings and were rated by 4 friends and up to 4 strangers in a round-robin design. Participants then completed a battery of behavioral tests from which criterion measures were derived. Consistent with SOKA model predictions, the self was the best judge of neuroticism-related traits, friends were the best judges of intellect-related traits, and people of all perspectives were equally good at judging extraversion-related traits.”

The great part about the Max Bazerman’s book is that he provides a step-by-step guide to breaking bad habits and spotting the hidden details that will change your decision-making and leadership skills for the better. The key is to learn what a blind spot is and why you are programmed not to notice it. What is the perceived value to your subconscious?

Additionally, you will learn how to pay attention better not only to what is going on but also to what is “NOT” going on. Often what is not going on is more illuminating than what is going on. By realizing and acknowledging that both you and the person you are negotiating with come from a place of self-interest — you will be able to identify possible compromises that take both your and the other parties’ interests into consideration. This helps to close the best possible deal and it will expand your life’s enjoyment as well.